About three years ago, I went for a trail run with a friend in the arid hills of Fuerteventura. When we reached the summit, he mentioned something that has stuck in my mind ever since. An elite ultra-runner friend of his had confided to him the secret of long-distance running: remember to look up to the sky. I recalled those words as I stood on the sand, with my running gear ready, at Playa Las Canteras.

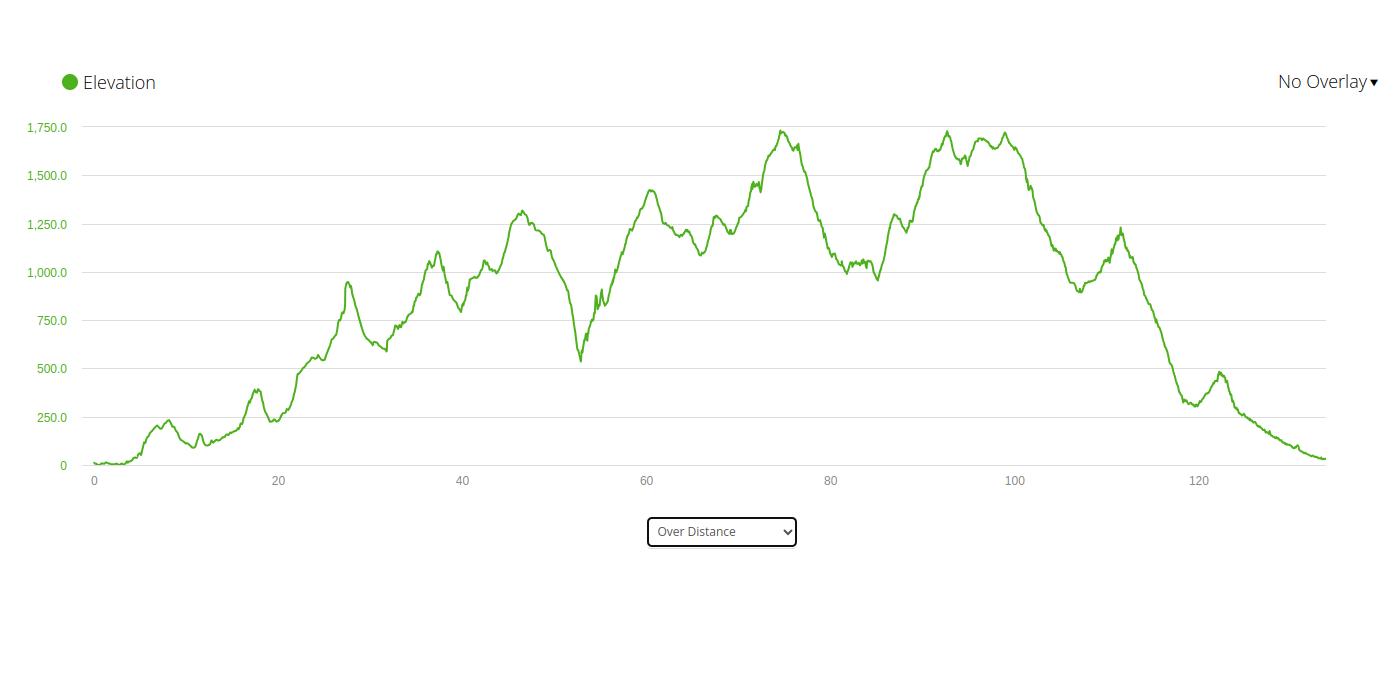

The night was chilly, windy, and rainy. There I was, alongside some seven hundred other people at the starting point of Transgrancanaria, a trail ultramarathon crossing the length of the island of Gran Canaria, from Las Palmas in the north to Maspalomas in the south. It covers a distance of 127 kilometers and ascends over 6800 cumulative meters. This would be my first trail ultra and also the first race I would attempt after overcoming some problems with plantar fasciitis,1 which prevented me from running for about a year.

The organizers called for the participants to join their respective groups, with the elites at the front of the pack. I felt like a rockstar when I realized that I was only a few meters behind Courtney Dauwalter. Immediately, I noticed my heart rate skyrocketing. Had I chosen the wrong race?

The Dreaded Email

Two days before the race was scheduled to begin, we received the email. The weather forecast predicted cold conditions, making it mandatory to carry our winter gear. In the weeks leading up to the race, I had read that, on average, it rains two days in February on the island. Naturally, I thought the chances were slim that winter gear would be required. But there I was, reading the dreaded email I had hoped to avoid.

I wasn’t looking forward to the email, not because of the weather itself but rather because of the extra weight that carrying the winter gear would entail: gloves, windproof trousers, thermal t-shirt, and long thermal pants. I’m someone with a high tolerance for cold weather, and carrying the extra weight was going to be annoying. Well, that was about to change.

The race began with some light rain in Las Palmas. I found myself comfortably towards the end of the pack. Soon, we began the ascent and left civilization behind. All I could see was the trail of headlamps and red taillights ahead of me. I arrived at the first aid station, Tenoya, comfortably within my plan-A time. The first 11.4km and 375m of cumulative ascent were behind us. But as the trail started to incline, my plans started to go downhill.

Hope for the Best, Prepare for the Worst

On the trail, the terrain dictates the speed you can maintain. Soon after leaving Tenoya, we expected some ascent but relatively flat terrain, perfect for gaining some speed. However, this section turned out to be a riverbed with stones the size of footballs, and the trail was narrow enough to prevent overtaking, even while power walking. Not that you would want to attempt it. Without careful attention to your footing, it was easy to twist an ankle. When in my life would it have occurred to me to run on a riverbed to train for the Transgrancanaria?

We made it to the second aid station in Barreto, with 19.3 km on our feet and 754m of cumulative ascent in our quads, and began our climb to Pico de Osorio, a steep hill with a narrow clay soil trail. The rain intensified, quickly causing a crowd jam. As we approached the summit, the rain made the path very slippery. People were falling onto their knees, and some opted to crawl until reaching the next rock or tree to grab onto.

I used the bottleneck as an opportunity to take out my jacket and finally acknowledge that it was getting cold. I eventually made it to the top by swinging from the branches of trees, reminiscent of my early relatives in the evolutionary path. Upon reaching the summit, we found that our shoes were now considerably heavier due to the added mud on our soles. It felt like Kangoo jumps, but without the bouncing.

On the way down, watching every step as we gained speed on the descent, it occurred to me: the weather in Las Palmas and Maspalomas, both coastal cities, is nothing like up in the hilly inner parts of the island. With these thoughts and my gloves, shorts, and jacket all wet, I realized we were in for a hell of a day. As we approached the aid stations in the town of Teror, I jokingly remarked to one of the volunteers, “No wonder this place is called Terror.” The volunteer smiled and kindly handed me some water. My notes read 31.4 km and 1580m of cumulative ascent so far.

Murphy’s Law

The sun rose around 7:30 am as I arrived at the fourth aid station at Fontanales. We already had 43km and 2541m of cumulative ascent on our legs. I grabbed my drop bag, managed to change clothes, and eat some of the food I had brought along. It was the first time I started noticing people distraught.

The rain had taken an emotional toll on some of us. I recall the eyes of a very young runner, looking much fitter than me, asking the volunteers for the bus back to Las Palmas. The rain had worn us down. I had changed into dry clothes, but all the winter gear I had was wet. The only thing I had left was the pair of windproof trousers, which I still carry dried in my backpack.

While eating, I overheard someone next to me, a man from Bilbao, opening his drop bag and joking about the amount of sunscreen he had brought for the race. “¡Qué estúpido!” he said as we both started laughing. I myself had made sure to pack lots of sunscreen. After all, we were going to be running on an island with an average February temperature of 20 degrees Celsius.

I finished my Red Bull and croissant and said goodbye to my fellow runner. Outside, it was cold and foggy, but the rain had subsided. It reminded me of the cold mornings in Bogotá while waiting for my bus to school. I left Fontanales with strong legs and a strong mind. I was still within my plan-A aspirations. I put my earphones on and started playing my ultramarathon playlist. Even though it was nowhere near sunny, I put on my sunglasses. After all, the weather couldn’t get worse than this, right?

Wrong. Very wrong.

Murphy’s Doppelganger

We soon started our first steep descent towards Barranco del Sao. The views were gorgeous. It was one of the few times I stopped to soak in the landscape. Next to me, appreciating the view, was a fellow runner. One of his trekking poles was broken. I shuddered at the thought of doing this race with only one pole. “One is better than none,” he mentioned with energy.

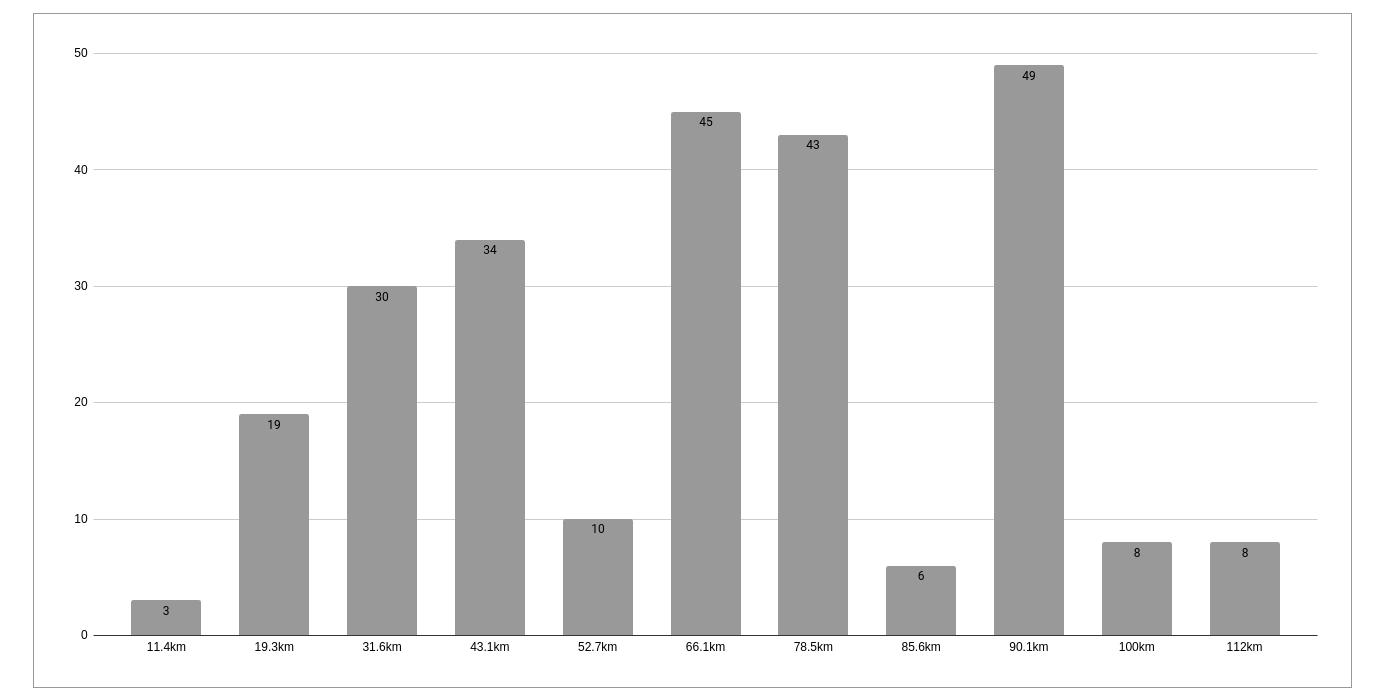

His optimism sounded foreign to me at the time. I would see this fellow runner about five times more throughout the race. I never found out much about him, his name, or place of origin. The only thing I remember is his resemblance to Oppenheimer’s Cillian Murphy. I was feeling strong and overtaking many of my fellow runners as we arrived at the fifth aid station, El Hornillo. With 52.7km and 3158m of cumulative ascent behind, I had gained one hundred and thirty-three positions.

While at El Hornillo, I noticed the notes I had brought with me were completely wet. It turns out, paper does not fare well in rain. I quickly turned to a volunteer and asked the distance to the next stop. “Solo siete kilómetros,” said the volunteer. I roughly estimated the amount of water I needed for the seven kilometers in my soft flasks and headed out.

When Life Gives You Lemons…

The merciless ascent began quickly. Soon, other runners started overtaking with a really good pace.2 The summit was nowhere in sight. “Which is the next aid station again?” I asked as they passed by. “Artenara,” murmured one of them. The news came as a thunderbolt. The distance to Artenara is actually 13.4 kilometers, I remembered. It was almost twice as much as I had accounted for in water. Furthermore, the stretch to Artenara is the second steepest and longest ascent of the race. There were the lemons.

That last debacle sealed my fate; I was not going to make it by plan-A time. The mountains in Gran Canaria have many false summits, where you think you have arrived at the top only to find out you are nowhere near it. The rain continued. It became difficult to breathe. It felt as if my throat was burning with every gulp of air.

Drinking water (the little I had) from my back water bag instead of my front soft flasks became my preference; it was warmer and alleviated, even if for a moment, the pain in my throat. “Is this what a DNF looks like?” I thought. I meditated on the hypothetical messages I would deliver to my friends and family as soon as I hit the next aid station and decided to quit. My soul was broken.

In what looked like a miracle, I made it to Artenara, the fifth aid station on the path. After 66.1 kilometers and 4216m of cumulative ascent. Physically impaired and emotionally destroyed. To add insult to injury, I had made it fast enough to see the last bit of warm food given to someone else. All I had left was fruit. One of the volunteers saw the despair on my face and offered some hot tea. I stood there, with no goal in mind. Am I really going to quit? But how else am I going to finish this thing? It is getting too cold, and I do not have a dry jacket or long sleeve with me.

…Channel Your Anger

Then I ran into Bilbao runner, who was just making his entrance to the venue. We exchanged rants for some time. He looked at his watch and pointed out, “it’s almost a miracle that we are 90 minutes ahead of the cut-off time for this stop.” That was some perspective, which quickly made me realize finishing the race is still possible. I shared with him that I was mentally broken, disappointed to be freezing while doing a race I expected to have mild to warm weather.

“Do you know what’s good for that?” Bilbao runner said, looking at me. “Get a bit angry.” And then it hit me. I felt entitled to have the conditions that I expected and was mad at the world for not meeting my expectations. How dare life give me things other than according to plan!? I realized how foolish my position was. I felt some relief.

I had hundreds of meters of ascent ahead, and it was promising to get colder as the night approached. I recall that, from my winter gear, I only had my windproof trousers with me. Keeping my torso warm was crucial as I was struggling to breathe. I figured warm legs could only help my overall condition. I struggled to put the trousers on, and when I was farther away from the public, I released a scream of frustration. That’s it. Let’s finish this race.

One Foot in Front of the Other

I left the checkpoint and began the climb towards Mirador Degollada de Las Palomas. Now rejuvenated by the lack of expectations, I accepted my new fate: to put one foot in front of the other. I quickly started recovering my pace uphill and gaining positions as we climbed. More importantly, I regained a sense of purpose.

This is one of the many reasons why we run long races. It’s a controlled experiment to test our resilience and give us the opportunity to decide whether to quit or keep going. By having to commit to our decisions, we transfer this learning into our daily lives. I had reached the lowest point, and I was coming out of it.

At over 1700 meters altitude, the weather became the worst I had seen all day. The 35km+ winds made my body wobble as they hit the crest of the mountain. Hail started falling, and branches were moving violently. At that point, I thought about that ultramarathon in China, where 21 runners died in the cold front.3

Descending mostly on my own, I passed day hikers who cheered me on. An older man stopped me and asked about the race. With a mixed sense of admiration and confusion, he wished me good luck and sent me off. In Tejeda, after 78.5km and 4940m of cumulative ascent, I grabbed some coffee and thanked the volunteers. At least we were running while many of these volunteers were at a standstill in the middle of the blizzard, guarding the safe passage of runners across the streets.

Leaving the aid station, I ran into Murphy’s doppelganger, still with one trekking pole, passing it from hand to hand. We calculated we had 3 hours until the closing of the next aid station. “You see, you never needed more than one,” I joked as he passed me on the last steep ascend of the race. He smiled, and that was the last I knew of him. I don’t know if he ever made it to the finish line, but his resilience was inspirational to me that day.

Age is Only a Number

The fog, wind, hail, and the sunset all merged, creating a mystical environment near the last summit, Roque Nublo, one of Gran Canaria’s most recognized attractions and the insignia of the race. When I reached the summit, it took me by surprise not to see the famous geological formation. Only then did it hit me: the words Roque and Nublo roughly translate to Rock and Cloud. I couldn’t care less, to be honest. I was happy to know we were starting the beginning of the end, as most of the rest of the race was downhill towards Maspalomas.

The night was upon us as I made it into El Garañon, with 90.1km and 6055m of cumulative ascent done. I turned off airplane mode to reach out to my family and friends who were following the race. The last time they heard from me, I was about to quit. Evidently, everyone was asking for updates. I let them know my current position and my rather positive state of mind. Next to me was a runner from Fuerteventura, who had reached a standstill. Despite the fact that he was quitting the race due to chafing issues, he was content with the outcome. “At my 55 years of age, this is quite a feat I am doing here,” he said. And I could not agree more. I not only hope to reach his age but also be doing these sorts of races still.

It is fascinating that ultrarunning gathers people of rather an older profile. The discipline also blurs lines between genders. You could be the fittest person out there, but if you do not have the mental resilience to stand up and move on, you will never make it. It reminded me of a lady named Stella, like my mother, who finished the Berlin 100 Meilen after me in 2021. She was 76 years old at the time. I left the aid station on my own and merged into the night again. It would be the second night with rain, I noted to myself as I downed a cold, alcohol-free beer I had snatched from my last drop bag.

Keeping Company

The descent towards El Tunte began, an 8-kilometer stretch of steep, rocky terrain. Technical terrain, as the lingo goes. With every step, my quads and knees painfully reminded me of the torture I had put them through during the day. At around 2 am, after 100km and 6204m of cumulative ascent, I entered El Tunte, where warmer weather welcomed us. The aid station was located in the main square of the city, and music played out loud from speakers. It was a full-on party, with locals and volunteers joining in dancing salsa. It seemed like no one noticed me pouring drinks into my flasks. They were all having fun, and I didn’t blame them. I would much rather be in their shoes than have them in mine.

I left El Tunte, and for the first time, I started feeling tired. I was sipping a mixture of Pepsi and Red Bull from my right soft flask, hoping to stay awake. Running mostly on my own on the dusty and rocky paths, I would sporadically see a head torch in the distance ahead of me. Being alone on the trail and downhill made it so that I had to concentrate even harder on where to step next. Still, despite the mental and physical fatigue, I tried to absorb the unique views around me. When else would I be virtually alone on a trail in the early morning hours in the middle of nowhere on an island?

I soon found myself jogging downhill behind another runner, one of the few souls I saw after passing the 100km mark. “Want to pass?” he shouted as he noticed our paces had equalized. “Not really,” I replied. Having someone closely ahead of you on such trails takes care of most of your navigation decisions, which is also dangerously what leads others to get off the trail by mistake. “Name?” said my newfound running companion. “Paulo,” I replied. “Nice to meet you, Paulo. My name is Anurag, but I go by Anu.”

Look Up to the Sky

Anu had come all the way from India alongside some of his friends to run the Transgrancanaria. We went back and forth on a wide range of topics, from work, tech, family, and running life. “You know, I checked, and I will be the first Indian to ever finish this race,” he said. I felt very happy for him. I soon wandered off to the idea if I had ever been the first Colombian at something. Maybe. But who knows. We both welcomed the conversation to combat the boredom from the monotonous trail.

In between the exchange of ideas, speeding at short stretches on the course, we reached Ayaguares, the last aid station with the last group of volunteers standing. It had been 112km and 6581m of ascent by then. The volunteers looked more tired than us. I must confess that I rarely watch foot races on my own. For once, I have not encountered a race where a friend or relative was running. I have always been running with them. I once ventured my way out to see Eliud Kipchoge run the Berlin Marathon 2023. I was bored out of my mind.

We must have sounded crazy to the passersby, as we were debating whether Sonia Gandhi was actually Indian or not, and the pros and cons of the BJP ruling all these years. Soon after leaving Ayaguares, we saw the lights behind the hills; they were the lights from Maspalomas, the finish line. We only had about 10 more kilometers on a flat riverbed. The same type of riverbed that makes you skip from rock to rock while avoiding the force of gravity on your ankles. “What is the definition of trail after all?” Anu wondered out loud as the rocks slowed us down. Whenever there was a chance to speed up in the process, he would take the lead and motivate me to catch up to him. Thanks to him, I improved my pace considerably in the last stretch of the race.

With only a couple of kilometers remaining to the finish line, he sped up and I let him go. “Are you sure?” he shouted into the darkness. “See you at the finish line,” I said, watching him use his trekking poles to push his body forward. I wanted to spend some time alone and reflect on all the things I had experienced throughout the day. Finally, I was able to look up to the sky.

-

I found out later on that those were runners from the Advanced Transgrancanaria, the 84km race, whose course mixed with ours for most of the length of the race ↩